* * * *

Author’s Note

This is a blog piece I wrote back in 2011. I never got around to writing this book and it is probably too late now because so many people have passed on that had an insider’s view of this history. I believe it is worth re-visiting the story, simply because Sandy Amoros was a historic Dodger that deserves to be remembered. All quotes attributed to this article were found in a Sports Illustrated piece written by Nicholas Dawiduff on July 10, 1989, titled ‘The Struggles of Sandy A.’

* * * *

There is a book out there that needs to be written. If I could take a sabbatical from work, I would attempt to write it. It is a story of triumph and tragedy. Of a person rising from the depths of poverty to the riches of fame and acclaim, only to return to the despair of destitution, homelessness, and loneliness.

It is a story that needs to be told of a man born in a foreign land in extreme poverty, left fatherless at the age of three and how he learned the game of baseball as a child and rose to prominence. It would chronicle his climb and progression in the sport as he ascended through the Cuban Leagues, the Cuban National Team, the United States Negro Leagues and eventually his acquisition with the Major League Brooklyn Dodgers. It would tell the story of a young Dodger scout named Al Campanis, who signed the young Cuban star immediately after witnessing his speed and knowing he had a star in the making before him.

Edmundo Isasi Amoros was born in 1930 in Matanzas, 50 miles east of Havana, Cuba. He descended from a rich Afro-Cuban heritage. A short ballplayer, listed at 5’ 7”, 170 lbs. He had decent pop for a player of his size and stature. Campanis recognized his amazing speed, bunting skill, defensive prowess and power that he generated from amazing wrist strength. “Miracle wrists” is what coach Billy Herman called them. Roger Kahn in ‘The Boys of Summer’ mentioned that. Camapanis remarked on Amoros’ speed saying, “I saw him hit a ball on one bounce to the second baseman and he nearly beat it out.” Amoros was bound for the big leagues on the fast track.

It would address the experiences he faced in the states, the racism of Jim Crow laws, the challenges of a new language and culture and how he still succeeded as a standout minor leaguer outfielder in the Brooklyn organization for clubs in St. Paul and Montreal.

As a youngster in Cuba, he witnessed the Dodgers training in Havana and was immediately taken by Jackie Robinson. Amoros soon began to pattern his game after Jackie, using his best asset; blazing speed and daring baserunning. Edmundo quickly rose through the ranks in the Cuban League and was selected as an outfielder on the Cuban national team. He led his national team to the championship of the Caribbean Games in Guatemala City in 1950 by hitting .370 with 6 home runs and twelve RBI in the series. Shortly thereafter he was signed by the Negro League New York Cubans. From there Campanis scouted and signed him to a contract with Brooklyn.

He progressed in the Minors, leading the International League in hitting with a .353 clip at Montreal. By 1954, he was the starting left fielder with the defending NL Champs. He hit memorable homers in a pennant-clinching victory and in game five of the ’55 Series.

It would cover his struggles in the Major Leagues on a team of superstars and future Hall of Famers and it would be a story told by his teammates that reached out and befriended the young man. Additionally, it would tell the story of the Cuban community in New York and how he sought refuge among them. And it would address the friendship with fellow Cuban teammate Chico Fernandez who would step up later in his life to assist him in a time of need.

Carl Furillo tried to speak Spanish with him and attempted to teach him English. Roy Campanella would joke with him and keep him company on road trips. Amoros was the only Latin player on that Brooklyn team for a time, but he never got a grasp on the English language and there are those that believe that held him back from becoming a standout player. Eventually, Chico Fernandez, his fellow Cuban and minor league teammate made the big club in 1956. They would jump in his car and go to Manhattan to Latin clubs for music and dinner. Brooklyn embraced the young star. The Dodgers were the perfect fit for the young Cuban with their diverse roster and history of innovation and integration. The borough was an ideal place for him to break into the Major Leagues.

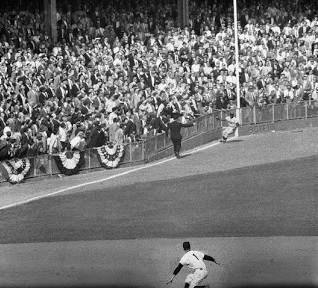

It would cover the baseball highlight of his life and how he was a World Series hero. The incredible catch and series-winning play in Yankee Stadium on October 4, 1955.

The catch ranks right up there with the greatest clutch plays ever. Game 7, Yankee Stadium. Dodgers up 2-0 in the 6th. Runners on 1st and 2nd with none out. Yogi Berra sliced a drive down the left field line. Amoros was playing him to pull in left-center field. Dodger pitcher Johnny Podres said, “I thought, Sandy, you better get on your horse to catch this one!” Berra stated,” If he wasn’t left-handed, he’d have never caught it.” Baserunner Gil McDougal, “…I was a dead duck.”

Amoros’ stabbing catch, cat-like reflexes, instant jarring stop, pivot, and return throw was instrumental in not only recording the out but turning a rally stopping double play. Three innings later, the Dodgers had won their first World Championship.

Then it would chronicle the celebration, as he returned home as a hero to Brooklyn and to Havana, Cuba.

Brooklyn was a borough in euphoria. Amoros returned to Cuba as a national hero. He was a source of national pride to Cubans. A World Series hero. A celebrity back home. Even as his career sputtered to an end, Amoros was beloved in his home country.

At the pinnacle of his life and baseball career, it appeared that Amoros’ future was very bright. But tragically from that moment on, Sandy Amoros’ life would start to slowly slide downhill with a series of setbacks, bad breaks, and adversities.

A biographical piece on Sandy Amoros would address his following years in the majors, his minor successes and eventual fall from elite status. Eventually resulting in a trip back to the minors and a trade from the only organization he knew, his return to his homeland and the changes he faced in Communist Cuba.

1956 was an average year for Amoros when he hit .260 with a career-high 16 homers. He even came within an eyelash of breaking up Don Larson’s perfect game. Larson in his book, ‘The Perfect Yankee’, (a batter by batter accounting of his perfect game), said Sandy’s slice down the right field line was within 3 inches of being a homer. But overall, it was a disappointing series and his 1 for 19 performance in the ’56 fall classic was a precursor of things to come. In 1957, his playing time diminished as rookie all-star Gino Cimoli replaced him in left field. By 1958 Amoros was back at Montreal in the minors. The following year he was traded to Detroit, where he was only called up to the big club for part of the 1960 season. After that, Sandy could only find a full-time baseball gig in Mexico, with the Mexico City Reds. Amoros finished his major league career being one week short of service time that would allow him to collect a major league pension.

It would narrate the story of his relationship with Fidel Castro. The job offer that he turned down to manage a team in the newly formed Cuban league, and the consequences he faced for standing up to the dictator. The stand he took against him and the eventual suffering and political persecution that he encountered because of it. It would address the confiscation of his property, the loss of all his possessions, the political persecution he faced and his struggle to return to the United States.

He was a national icon in Cuba. A hero everywhere he went. Children idolized him and in that baseball crazy country, the world was on his shoulders. But then the revolution happened and things changed. In 1960, during a friendly pick-up game amongst friends, Fidel Castro arrived, with camera crews on hand, he wanted to participate. “Before Castro showed up we were going to have a good game,” says Amoros. “When he came, we had to do differently. We were better players, so it wasn’t fun anymore.”

In 1962 Fidel Castro approached him to be the manager of one of the teams in a newly created Cuban League that Castro created. There had been talk about Cuba getting an expansion Major League team, but with the change in political climate, that would never happen. Amoros was still playing and he wanted to continue doing that by going to Mexico City again. “I told Castro I didn’t know how to manage. I could play, why would I want to manage?” Privately, Amoros had qualms about working for the government. Castro did not take Amoros’s refusal lightly. He stripped Amoros of his ranch, car, all his assets, and cash. Amoros was detained in Cuba and not permitted to report for the 1962 Mexican League season. “Castro would not let me out,” he says. “I don’t want to talk bad about him.” In 1981, Amoros told The Sporting News, “I don’t like the guy. I thought he was loco. When I refused [to manage], that’s when the trouble started.”

A story on Sandy Amoros would tell the story of the Brooklyn Catholic Charities group that stepped up and sponsored Amoros so that he could obtain a visa to return to the United States in 1966.

It would discuss his deteriorating health, his severe diabetes, his drinking problem, and the loss of his marriage and family.

Amoros’ decision to reject Castro’s offer cost him deeply. His celebrity was now underground. He and his family lived a life concealed from Cuban society. “I hardly left my house except to go to the corner. I did not go to restaurants or cabarets. Sometimes to the movies. But they are putting on Russian and Czech movies, and I did not understand them well. We lived on two pounds of rice for a month in Cuba. One pound of meat for two weeks. Beans? Two pounds a month. For me, Cuba was better before. Castro wanted my daughter to enter a youth organization, but I didn’t let her.”

A drinking problem developed as Sandy’s restricted activity brought on a deep depression. Permitted to leave in 1967 along with 64,000 other Cuban outcasts, Brooklyn Catholic Charities sponsored Sandy’s family and provided him a coaching job within the Catholic Youth Organization.

Buzzie Bavasi heard of his plight and consulted with Walter O’Malley. It was agreed, the Dodgers offered to place him on the 25 man roster for one week so that he could earn a Major League pension. He brought the lineup card to home plate for one week. Amoros, who had been nicknamed “Sandy” while a minor leaguer, due to his muscular physique and similar appearance to a popular boxer of the era, Sandy Saddler, was merely a shell of what he used to be physically. He weighed 140 lbs. Diabetes was affecting his deteriorating health. After a nine-day period in which he followed the Dodger team to Houston and Philadelphia, he returned to the Bronx where he had a job at a T.V. and electronics store. But the alcoholism took its toll and his wife and daughter left him and went to Miami. Shortly thereafter, the store he worked at burned to the ground and he was jobless.

Again, aid arrived as New York Mayor John Lindsey was tipped of his dilemma and he provided him employment in the city’s recreation department. That job served as his source of income until Lindsey left office in the early 1970s. Unemployment followed and deteriorating health as well. His leg killed him, but pride kept Amoros from letting anyone know. As his MLB pension started to arrive in 1977, Amoros moved to Tampa and lived off the $450 check and menial labor jobs that he could find.

Amoros ignored the leg problem for ten years until it was impossible to do so, and by then it was too late. Forced to check in to a Tampa hospital in 1987, gangrene and circulation problems forced doctors to amputate below the knee. Former teammate Chico Fernandez heard of his situation and contacted Joe Garagiola and Ralph Branca at MLB Baseball AssistanceTeam (BAT). They were instrumental in paying Sandy’s medical bills, finding him an apartment and an artificial leg.

Periodic appearances at Vero Beach Spring Training events and in signing ceremonies supplemented Amoros’ income. He took pride in his baseball achievements. The lone picture mounted on his wall in his Tampa apartment was a framed photo commemorating his catch, given to him as a gift at a Dodgers Spring Training event in 1985. But in his last days, he lived in need of assistance in a barren apartment. Eventually Sandy moved in with his daughter in Miami when pneumonia and the deteriorating diabetic condition made him completely unable to care for himself. Sandy died there on June 27, 1992, a few weeks before he was supposed to return to Brooklyn for the Coney Island Sports Festival. An autograph signing and memorabilia auction was set up, where the proceeds were to help defray his medical costs. He never made it.

* * * *

I set this project aside about a year ago I had started doing the internet research on it and realized to give it a real chance, I’d need to travel to the backroads of Cuba and to the areas of Brooklyn, Miami, and eventually Tampa where Sandy resided in his last days. I’d need to seek out former major and minor league teammates that as time passes, are passing away each year. This is a story that needed to be told. but with proper dedication, research and time. Time is running out, witnesses to this great story are advancing in age. I hope it isn’t too late, for the time being, this post will have to suffice.

Rest in peace Sandy.

* * * * *

December 19th, 2019 at 8:00 am

December 19th, 2019 at 8:00 am  by Evan Bladh

by Evan Bladh  Posted in

Posted in

Thanks for this very interesting article Evan, I wish you luck in completing this project.

thank you for a terrific article! I hope you will reconsider and write the book, even if you are unable to get all of the detail. Not only a book, this is would make for a top notch movie

Greatest defensive play in WS play! Turned a Yogi Berra double into a double play (Sandy to Pee Wee t… https://t.co/Ae06MIm7hb

When I became a Dodger/baseball fan in 1961 one of the very first things I learned of was The Catch. And I learned that an otherwise unheralded player can do something that a hall of greats could not. I also recall a 1967 radio broadcast when Vin recounted the terrible experience Sandy had back in his homeland under Castro, even having his 1955 World Championship ring confiscated. And I learned the Dodgers had a replacement made when they placed him on the roster to qualify for his pension. Once a Dodger, always a Dodger.

Such a sad story. I was at the 4th game of the 55 series. I just told another Dodger fan that, while discussing Erskine’s role in that game (I had a conversation with Erskine not too long ago), what I remembered about the game was Snider and Amaros. Strange.