The Los Angeles Dodgers are one of very few professional sports franchises to carry the distinction of having drawn more than three millions fans (based on ticket sales) many times over the past six decades. In fact, they have done so a total of 33 times since the franchise moved to Los Angeles from Brooklyn in 1958 and have done so in each of the last eight consecutive seasons. And even though baseball fans from around the world still marvel at the incredible beauty of baseball’s third oldest ballpark after its 56th season, many are completely unaware that the construction of Dodger Stadium almost didn’t happen, and even fewer are aware that beloved Hall of Fame broadcaster Vin Scully actually played a key role in making it happen.

Is this true? Did Vin Scully actually have this kind of juice even back in 1958?

The short answer is yes, but as you might have guessed, there is a lot more to this story.

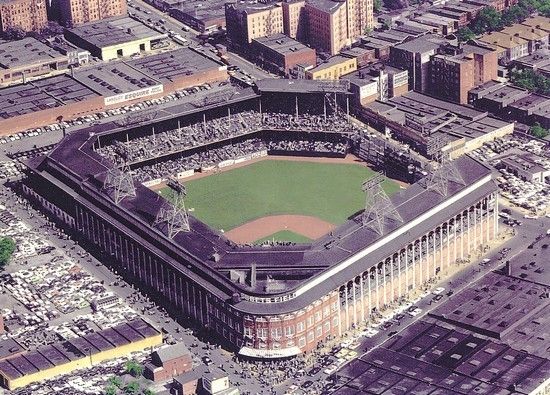

Although many longtime Brooklyn Dodger fans still blame former Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley for moving their beloved Bums from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in 1958, the truth of the matter is that O’Malley, who was born and raised in Brooklyn, did everything that he possibly could to keep the team in the borough. Unfortunately, New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, who had tremendous power and say regarding land and construction projects in New York City, absolutely refused to allow O’Malley to build a new stadium in Brooklyn to replace the extremely outdated Ebbets Field – this in spite of the fact that O’Malley agreed to finance the new stadium entirely out of his own pocket.

New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses did many great things for the City of New York, but he did absolutely nothing to help Walter O’Malley keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn. (AP Photo)

Believing that O’Malley was bluffing about actually moving the Dodgers out of New York, Moses refused to back down and instead offered the Dodgers owner land near Flushing Meadow to build his new stadium – land on which Shea Stadium was eventually build and where Citi Field stands today; land that is in the borough of Queens not Brooklyn. (Somehow the Queens Dodgers or even worse, the Flushing Dodgers, doesn’t have a very good ring to it).

But O’Malley was not bluffing – it was either Brooklyn or move the team to Los Angeles, where city officials had been courting the Dodgers owner since 1956 and were more than willing to work with him on acquiring land for a new stadium. Thus, it was Robert Moses who forced O’Malley’s hand and on September 24, 1957 the Dodgers played their final game at Ebbets Field.

The Brooklyn Dodgers played their final game at Ebbets Field on Tuesday, September 24, 1957 in front of 6,702 fans beating the Pittsburgh Pirates 2-0. (AP photo)

The move to Los Angeles wasn’t without its problems for O’Malley; in fact, there were huge problems. While L.A. City officials welcomed O’Malley and his Dodgers with open arms, many others did not – most notably a man named John Smith who owned the San Diego Padres, a Triple-A team in the Pacific Coast League. It was Smith’s contention that allowing the Dodgers to build their own stadium in Los Angeles would be an economic threat to his minor league franchise – a franchise that would one day itself become a major league expansion team.

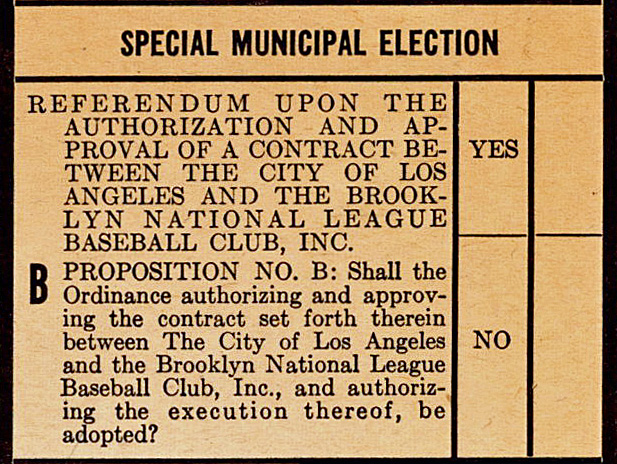

To compound matters, resistance to O’Malley’s plan to build a new stadium near downtown Los Angeles was intense because the land on which the city had approved for the proposed construction of Dodger Stadium, Chavez Ravine, was home to hundreds of low-income residents and undocumented workers who would be forced to leave their homes – many of which were without running water or electricity. As a result, opponents of the new stadium forced the matter to be put before L.A. voters in a referendum titled Proposition B.

Proposition B as it appeared on the June 3, 1958 ballot.

(Image courtesy of griddle.baseballtoaster.com)

Although it wasn’t discovered until after the election, the driving force lobbying against Proposition B was none other than John Smith.

So how does Vin Scully play into all of this?

This excerpt from Neil J. Sullivan’s outstanding 1989 book The Dodgers Move West pretty much sums it up:

“Perhaps the most formidable asset which Walter O’Malley might have brought to bear in support of Proposition B was the Dodgers’ announcer, Vin Scully. Scully was immediately popular in Los Angeles, and with the team doing so poorly [in 1958] he became the focus for much of the enthusiasm about the team. He was the only member of the Dodgers having a good year. Scully relates that Walter O’Malley never discussed the political contest with him, nor suggested that Scully try to sway voters during his broadcasts. Such an attempt might have been received as a crude measure and triggered a backlash, but the tactic was apparently never even considered. Scully also reports that he personally felt no responsibility for the outcome of the referendum. He maintains he didn’t consider the seriousness of Proposition B until after the election was over. Up to that point, he was as unaware as Walter O’Malley about the exercise in direct democracy, and only later realized how fragile a hold the Dodgers had on Los Angeles. The announcer’s innocence served the Dodgers very well.”

Although no one knew it at the time, Scully’s relationship with L.A. Dodgers fans would have a huge impact on the future of Dodger Stadium. (AP photo)

In the largest turnout for a non-presidential election (62.3%), Los Angeles voters passed Proposition B by the slimmest of margins – 351,683 in favor, 325,898 opposed, a difference of only 25,785 votes – not even the average attendance of a single Dodgers game. Had the ballot measure failed, the Dodgers, in all likelihood, would have moved elsewhere – most likely Minneapolis, which was lobbying hard for an MLB team and eventually landing the Washington Senators and renaming them the Minnesota Twins. (Can you even imagine?).

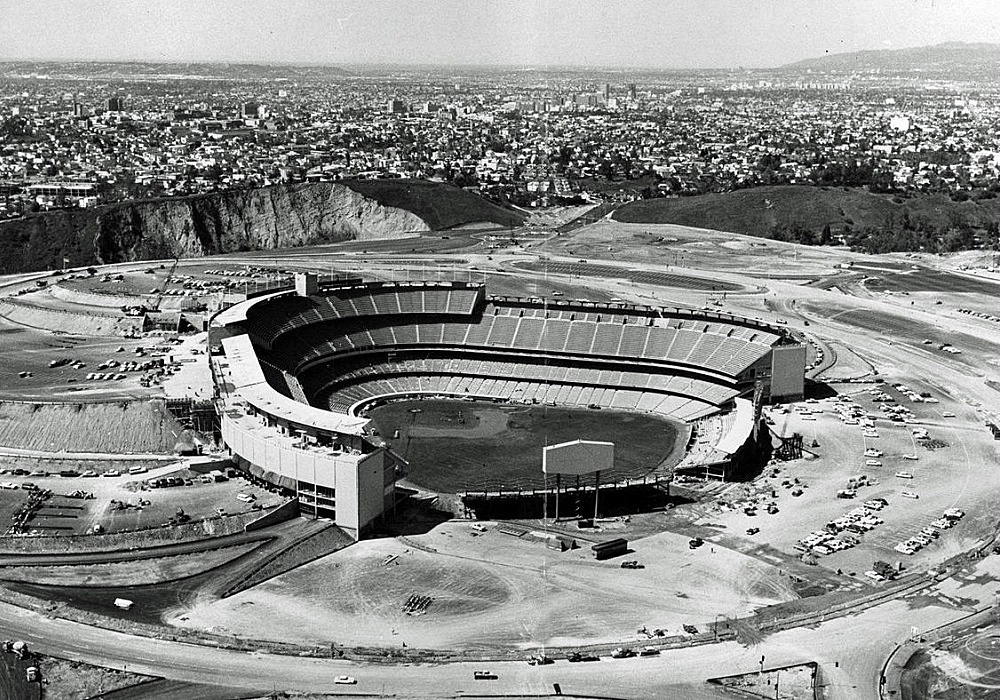

This photo of Dodger Stadium was taken only weeks before Opening Day 1962.

(AP photo – Click on image to enlarge)

Vin Scully has been very close friends with the O’Malley family for over 67 years.

(L to R: Peter O’Malley, Jo Lasorda (Tommy’s wife), Sharon Hough (Charlie’s wife) Yvonne Stephenson (widow of former Dodger Jerry Stephenson), Vin and Annette O’Malley (Peter’s wife).

(Photo credit – Ron Cervenka)

Did Vin Scully’s immediate love affair with Dodgers fans, even brand new Los Angeles Dodger fans, have a direct impact on the final outcome of Proposition B?

I’ll let you be the judge of that.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

(Article re-posted from June 27, 2016)

November 24th, 2018 at 8:00 am

November 24th, 2018 at 8:00 am  by Ron Cervenka

by Ron Cervenka  Posted in

Posted in

Thank you for a great article! I highly recommend the book, “The Last Good Season” by Michael Shapiro which chronicles the Brooklyn Dodgers 1956 season including O’Malley’s efforts to keep Dodgers in Brooklyn.

Eminent domain refers to the power of the government to take private property and convert it into public use. The Fifth Amendment provides that the government may only exercise this power if they provide just compensation to the property owners.

Interesting history regarding the acquisition of the Dodger Stadium land. The Dodgers and Dodger Stadium have been a BOON to the City of Los Angeles. Were the residents of Chavez Ravine adequately compensated? My boyhood home was razed to build the Simi Valley Freeway around 1968. My parents never felt they were provided “just compensation” by the government.

I regret having never asked the parents how they voted on Proposition B.

I remember reading an article (NPR as I recall) about LA acquiring the property referred to as Chavez Ravine in the early 50’s for the purpose of building public housing. With the election of a new mayor who did not support public housing the original plans were abandoned after much of the property had been acquired.

As a Brookynknight and lifetime Dodger fan, I remember being against the Dodgers moving to Queens. Now I realize how dumb that was. If that would’ve happened the Dodgers would’ve played their home games just a short ride away on the Number 7 train, from my home.

When I turn on my TV to watch the team play, as I did when they played in Brooklyn, it doesn’t seem that much different, though.

‘cept they’re in color now.

That’s right, I didn’t think of that.