As a youngster growing up on the east coast of Canada in the 1950’s I fell in love with the Brooklyn Dodgers. There was just so much to love – Duke, Campy, Jackie, Newk, the two Carl’s, Gil, Pee Wee and the list goes on. Don Drysdale was just starting to come into his own before the move to Los Angeles and Sandy Koufax had not yet blossomed. However, there were other lesser known players that I always appreciated for the roles they played in the success of the Brooklyn Dodgers – Clem Labine, Jim Hughes, Billy Cox, Sandy Amoros, George “Shotgun” Shuba, Jim Gilliam and others.

One of the lesser lights that particularly still stands out in my memory of those years with the Brooklyn Dodgers and later as a member of the Los Angeles Dodgers was “Mr. Versatility” and I think the prototypical utility player before the role was so defined and embraced by MLB.

Jim “Junior” Gilliam was, in my opinion, the first real Dodger utility player and most certainly so in my lifelong career as a Dodger fan which now spans almost 65 years. Some will argue that Gilliam was not a utility player because he played his first two years with the Dodgers at second base. However, even in his second year he began to branch out to other positions. Gilliam was indeed a utility player able to play several positions competently over the course of his career and with the confidence of his manager.

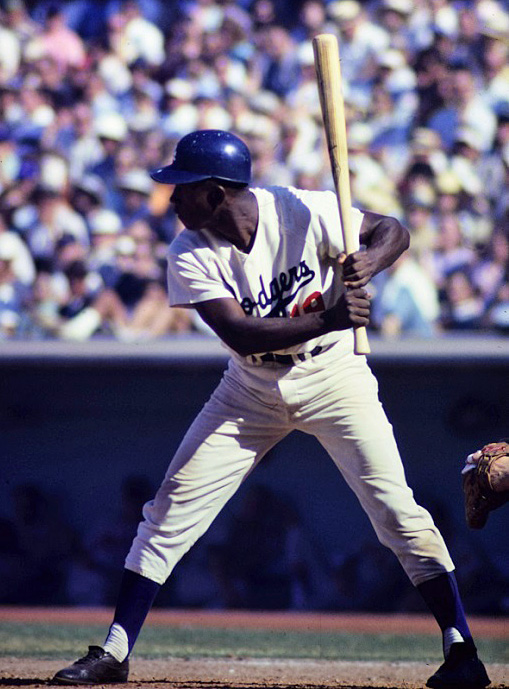

Jim Gilliam – “Mr. Versatility”

(Getty Images)

As a black player Jim Gilliam’s path to major league baseball was not much easier than that of Jackie Robinson’s although Robinson had blazed a trail for him. However, his determination to not only get there but to excel as a major league player was not unlike that of his black teammates – Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe and Joe Black.

Gilliam was born in Nashville, Tennessee on October 27, 1928 and attended Pearl High School in Nashville. His early life was not easy as his father died when he was only two and his mother had to do house work to provide for him, her only child. She was able to buy him his first baseball glove when he was 14. Within two years he was earning a return on that investment by playing for the Crawfords, a local team, and getting paid to do so.

In 1946 just three years after getting his first glove Jim Gilliam got a tryout with the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro National League. The tryout became a defining moment in his baseball career. Only 17 years of age at the time he made the team but perhaps more importantly Baltimore’s manager, George “Tubby” Scales, noticing that Gilliam had trouble hitting curve balls from a right-handed pitcher simply told him to go to the other side of the plate and a switch-hitter was born. Additionally, Scales addressed the youngster as “Junior” and he became known as “Junior” Gilliam.

By 1950 he had been selected as an all-star three times to compete in the East-West Games. By now he was getting noticed by major league teams and a Chicago Cubs report stated he was “the best young prospect in the [then] Negro American League.” The scouting report advised Gilliam was “a clean-cut youngster with an accurate snap throw, a good eye, a hustler with the knack for punching the ball to all fields.”

Gilliam’s contract was purchased by the Cubs but for whatever reason it was decided he wouldn’t make it with the Cubs. One suggestion was that he wouldn’t be able to hit AAA pitching. Another was that the Cubs had a better prospect so there was no place for Gilliam to play. However, his future room mate with the Dodgers, Joe Black, felt that the reason was because he hadn’t played integrated ball and being socially shy the Cubs believed he could not adapt to major league baseball.

Fortunately Gilliam was signed by the Dodgers in 1951 and by 1952 – at age 23 – he became the International League’s MVP. Playing for the Montreal Royals he hit .303 while leading the league with 133 runs scored along with 41 doubles and driving in 109 runs.

The Dodgers were looking for a lead off hitter and it was his plate discipline that paved his path to Ebbets Field. With the AAA Royals in 1952 Gilliam walked 100 times while striking out only 18 times.

By the end of his rookie season with the Dodgers in 1953 he had started 146 games, been on base in 130 of them, and scored 125 runs along with a. 278 batting average, a .383 OBP and a .415 slugging percentage. He led the league with 17 triples and 710 plate appearances. Gilliam walked 100 times in 1953 setting a new walks record for rookies. At the end of the season he was selected as the National League Rookie of the Year.

Jim Gilliam played 14 years with the Dodgers, the last two in 1965 and 1966 as a player-coach. He retired after the 1966 season and continued to coach with the Dodgers through manager Walter Alston’s reign which ended following the 1976 season. Tommy Lasorda and Jim Gilliam were the two leading contenders to replace Alston. Lasorda got the call and asked Gilliam to remain with the team as a coach. That was to be Gilliam’s only managerial interview.

He never evolved into a star player, at least statistically, and some say it is because he played baseball the year around playing winter ball in Latin America between MLB seasons. However, he did evolve into the quintessential but yet undefined utility player. During his career, all with the Dodgers, he played 1,046 games at second base, 761 at third base, 203 in left field, 29 in right field, five in center field and two at first base. Offensively he accumulated 1,889 hits while walking 1,036 times and striking out 416 times finishing his career with a .265 batting average and an OBP of .360. He hit .266 from the left side and .261 as a right-handed hitter. By comparison, today’s super utility player Ben Zobrist, has a career batting average of .265 and an OBP of .355.

Gilliam was part of trade rumor speculation practically every season he played with the Dodgers. He started every season after his first one not being the leading candidate for any starting position, but for the 12 seasons until he became a player-coach, he averaged 146 games played. In true Jamey Wright fashion he had to win a spot each and every year after his rookie year. He was actually released by the Dodgers in both 1964 and 1965 and resigned as a free agent.

The 5’10” -175 lb switch-hitter had a baseball acumen that did not go unnoticed by his manager and fellow players. His greatest supporter was manager Walter Alston who perhaps above all others saw the need to keep Gilliam in the line up at some position because of his reliability, versatility, and durability.

First baseman Ron Fairly explained Alston’s fondness for Gilliam: “He never missed a sign; all the years he played for Alston, Walt would say the one player who never missed a sign was Jim Gilliam,” Fairly stated.

In 1961 Alston added: “He gets on base. He can punch the ball on the hit and run. He steals and never throws to the wrong base. He knows how to get a walk. He has all the little things that go to make up a good ball club. I don’t think he’s ever been late a day in his life.”

In 1962 Dodger shortstop Maury Wills stole 104 bases and was caught only 13 times. Little did we know that Wills was not working alone; he had Jim Gilliam batting behind him aiding and abetting in his thievery with a skill not gifted to many.

“I try to help him,” said Gilliam. “Lots of times there are pitches I could swing at, but I see Maury out of the corner of my eye and take the pitch if I think he’s going to get the base. Or else I’ll take a strike, even two strikes to give him a chance to steal it. If it looks like he could be caught, I’ll hit at the pitch. Maybe I’ll punch it through and Maury’ll be able to make it to third. Or else I’ll foul it off and he’s not out.”

There is no argument that Gilliam had a lot to do with Maury Wills stealing 104 bases in 1962.

(AP photo)

“Not a man in baseball can do it better,” said coach Leo Durocher, “because Jim’s a real mechanic with that bat. He’s the best two-strike hitter in baseball.”

Bill James created a measure designed to be a proxy for Baseball IQ, a stat he called “Player Performance Index,” a combination of specific batting, running and defensive statistics meant to pull out “percentage players.” Gilliam ranks third all-time for that measure, behind only Cincinnati Reds second baseman Joe Morgan and Philadelphia Athletics second baseman Max Bishop.

Jim Gilliam’s life ended all too soon at the age of 49. On September 15, 1978 he drove manager Tommy Lasorda to Dodger Stadium and then returned home. He suffered a cerebral hemorrhage at home. He later died on October 8th one day after the Dodgers won the National League title.

Los Angeles Times sports columnist Jim Murray penned a tribute to Jim “Junior” Gilliam and began his tribute with these words: “I guess my all-time favorite athlete was Jim Gilliam. He always thought he was lucky to be a Dodger. I thought it was the other way around.”

Jim Gilliam’s number “19” was retired on October 10, 1978. Among the ten Dodgers to have had their number retired he is the only one not to have been elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. If there was a Hall of Fame for utility players, James William Gilliam would be a solid choice to be the first inductee.

April 25th, 2016 at 6:00 am

April 25th, 2016 at 6:00 am  by Harold Uhlman

by Harold Uhlman  Posted in

Posted in

TERRIFIC article! I am going to copy and save for future reading and sharing with my grandchildren. THANKS! I remember Walt Alston saying that Gilliam was one of the finest ballplayers he had ever seen.

I agree, SUPER article! My first memories of Gilliam were in the early sixties. As the article says he batted second, he was HUGE in giving Wills lots of opportunities to steal. I don’t think I appreciated how good he was in those days. I was comparing him to Tommy Davis and that batting average and those RBI’s. I now wonder how many of those RBI’s were Gilliam.

I knew he was good at handling the bat, but, had no idea how good. The OBP and lack of strikeouts is awesome. I like the picture showing him choking up on the bat. Wish more hitters would do that with two strikes, you listening Joc. Hope the new Dodger player development department comes up with a “Gilliam 101” class.

Gilliam was a huge part of my early years as a Dodger fan. He and Maury were about as automatic as they came and the original source of “Get ’em on, get ’em over, get ’em in” (he was the get ’em over part).

He is also the strongest argument for Hodges, Wills, Fernando and Garvey to have their numbers retired by the Dodgers.

Great piece, Harold. Thanks!

I too really like the choke up on the bat to cut down on swing time and better bat control.

Love this quote by Walter Alston: “He doesn’t make any mistakes…He gives you 100 percent, day in and day out. He never moans. He’s a good team man. If I had eight like him, I wouldn’t have to give a single sign.”

Boxout7 – I also tended to compare him to other Dodger hitters but listening to games out of Brooklyn until the end of the 1957 season and in WS play a lot was made of the the little things he did to win games. I came to value him then and loved his baseball cards. He never seemed to look any older.

Yes, that is high praise from Alston. I also liked Durocher’s comment, pretty much says it all!

It is a shame so few players choke up these days. I was watching a game this weekend, probably Dodger game. And the announcers were talking about how hitters liked to put their little finger off the end of the bat. Said it gave them good whip action, didn’t say it gave them bat control. With all the defensive shifts these days, some bat control would be good. However, I did wish I had tried the pinkey off the bat in slow pitch softball (at least once).

I loved Dodger baseball cards, I think I still have Gilliam’s 1960, 1961 and 1962 cards. I know I can still see them in my head.

Bluenose Dodger, are you Harold?

Yes, we are one and the same. The Bluenose handle is specific to my part of the world in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, Canada which is the home of the famous racing schooner – “Bluenose”.

Lunenburg

Looks beautiful there, Harold.

I googled “Bluenose Schooner” very interesting! I wish Dodgers would go on a “Bluenose” style win streak!!

Thanks for doing that. We are very fortunate to live where we do even though it keeps me four hours away from the Dodger game time on the west coast.

I have his 1954, 1955 and 1964 cards. The 1955 Topps card is my favorite.

Many times I refer to 7 magnificent Dodgers as Hodges, Robinson, Reese, Cox Campanella, Furillo and Snider, I leave out Gilliam. That’s a big mistake, I make. Great article, Harold.

Fantastic article, Harold.

Harold, you knocked it out of the park. Wow! Love the Bill James stat on player IQ. Not surprised that Gilliam was ranked so high. One has to wonder what Dodger history would have been like had the O’Malleys selected Junior Gilliam over Lasorda. Lasorda would have gone to Montreal to manage and maybe the Dodgers win the World Series in ’77.

It’s been a long day and I’m just sitting down to read this.

What a fantastic article, Harold! As usual, you never disappoint with your highly informative and in-depth research.

Thank you for sharing the details of his playing career with those of us, like me, who only remember Gilliam as a base-coach with the team. I was certain there was more to the player, but never understood the full scope of his versatility.

I was 9 years old in 1962, but I remember Junior Gilliam. In 1963, I saw him in person for the first time and even at 10 years old, I knew this cat was different. I remember his last two or three years where he really was a sub, but you still knew this guy was a different breed. What a team player.

Great Article – Harold. Classic!

Thank you, Harold, for this piece on one of my all-time favorites. There were some of us who were aware how much he helped Maury and others. That really encouraged me to play with a team attitude.