(Re-posted from January 25, 2013)

On April 12, 2013, the highly anticipated movie “42” will premier in theaters nationwide. What many baseball fans may not realize is that this likely Oscar nominee about Jackie Robinson breaking baseball’s color barrier could have very easily been entitled “14” instead.

In 1942 Branch Rickey joined the Dodgers as the team’s president and general manager. He quietly and in a very determined way began his quest to bring black players to the team. He was well aware of the challenges that lay ahead trying to integrate the first segment of American society – baseball. He knew there would be resistance in the Commissioner’s Office, from other team owners, the players themselves and it would be difficult to predict the fan reaction. Most importantly would be selecting the correct player to meet the unbelievable challenges that lay ahead. The rest is history and we all know the correct player, perhaps one among a number of choices, was selected to battle prejudice and segregation in major league baseball.

What we might not have known was at the same time Branch Rickey was smoothing out the wrinkles in his plan to integrate major league baseball, a parallel story was unfolding. Bill Veeck, perhaps baseball’s greatest innovator, had a long time interest in the Negro Leagues and also had a close connection to the famous Harlem Globetrotters.

In 1942 Veeck (that’s Veeck–As in Wreck) developed a plan to buy the struggling Philadelphia Phillies and stock the team with black players. He made his plan known to Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis feeling confident that Landis would support the plan. Veeck was positive the plan could not be rejected when young black men were fighting and giving their lives for their country during WWII. Veeck miscalculated the segregationist venom of Landis. By the time he arrived in Philadelphia he learned the team had been taken over by the league. Veeck, with sufficient financial backing to buy the team, was not to be the new owner and integration of MLB was put on hold.

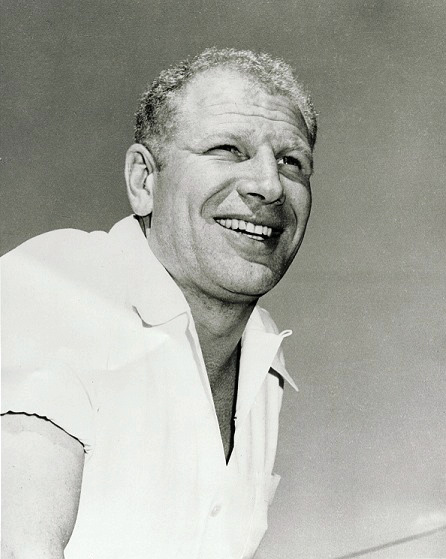

Known as Baseball’s Greatest Maverick, Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck tried to break baseball’s color barrier several years before Branch Rickey. (AP photo)

In 1946 Bill Veeck realized his dream and became the owner of the Cleveland Indians. His plan to bring a black player to the Indians developed quickly, but not quickly enough to become the first team to have a black player on its MLB roster. Following a speech in Ohio in 1947, Veeck was asked what he thought the chances were of Jackie Robinson making it as a major Leaguer. Veeck responded he did not believe Robinson would fare very well. When asked if the Indians would soon have a black player on their roster, Veeck responded that he would integrate the Indians’ roster if he could find a black player with the necessary talent level.

Veeck obviously didn’t want to make known his plans in the press but he had already begun efforts to find that young, talented player from the Negro leagues. Besides being a skilled player, such a player would have to have Jackie Robinson personal qualities, able to withstand the taunts and pressure of being the first black athlete in the AL.

Enter Larry Doby, a young versatile player with the Newark Eagles, who had just returned from his service in the navy. He was just the player for whom Veeck was searching. One wonders why the Dodgers were not interested in Larry Doby, whose home park was just twenty miles from Brooklyn. It turns out the Dodgers were quite aware of Doby and rated him as their top young prospect in the Negro league. However, Branch Rickey was most likely unaware of Veeck’s interest in black players and felt there was no rush in signing Doby, who was just 23 at the time.

Larry Doby could very well have been MLB’s first black player had Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck known what Dodgers GM Branch Rickey was up to. (AP photo)

Bill Veeck was in a rush. Whereas Rickey gave Jackie Robinson a full season with the Montreal Royals to prepare for his entry into major league baseball, Veeck felt a quick arrival in Cleveland would help minimize the pressures Doby would feel. That is, without any publicity, one afternoon as the Indians came onto the field; there would be a black player with them – Larry Doby. The rights for Doby were purchased from The Newark Eagles for a total of $15,000 – $10,000 outright and $5,000 additional if Doby stuck with the Indians for thirty days.

Larry Doby debuted with the Indians on July 5, 1947, just three months after Jackie Robinson debuted with the Dodgers. Like Robinson, Doby had his own Pee Wee Reese to lean on for comfort and support him. This from Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, who had once interviewed Doby: “…but (Doby) did tell me about Joe Gordon and always spoke highly of him. Doby told me that the first day he went on the field to warm up with the Indians, no one would throw with him. But Gordon stepped up and said, ‘I’ll play catch with you.’ Doby spoke in glowing terms about how much that meant to him. Because Gordon was an All-Star, many of Doby’s teammates fell in line after that.” Just as Pee Wee Reese had befriended Jackie Robinson, Joe Gordon had befriended Larry Doby, making his transition from the Negro Leagues easier. It is reported that from that day on, Larry Doby never went on the baseball field without reaching down and picking up the glove of his teammate Joe Gordon and handing it to him.

Larry Doby, as did Jackie Robinson, gave his heart and soul for his team, his family and most of all for all the black baseball players who came after him. When he first joined the Indians, some of his teammates refused to shake his hand, yet he always refused to say who they were. He and his family were forced to live apart from the team in Spring Training camp because of segregation rules. He often had to stay in separate hotel facilities and eat in separate areas from the rest of his teammates. In one instance, after being tagged out at second base, the opponent spit in his face. Doby walked away, not giving in to the evil of prejudice. Lou Brissie, a pitcher for the Philadelphia A’s in 1947, recalled in an interview with Ira Berkow: “I was on the bench and heard some of my teammates shouting things at Larry, like, ‘Porter, carry my bags,’ or ‘Shoeshine boy, shine my shoes,’ and well, the N-word, too. It was terrible.”

Larry Doby was counseled by Bill Veeck, just as Jackie Robinson was counseled by Branch Ricky. Doby explained in an interview: “When Mr. Veeck signed me, he sat me down and told me some of the do’s and don’ts…. ‘No arguing with umpires, don’t even turn around at a bad call at the plate, and no dissertations with opposing players; either of those might start a race riot. No associating with female Caucasians’–not that I was going to. And he said remember to act in a way that you know people are watching you. And this was something that both Jack [Robinson] and I took seriously. We knew that if we didn’t succeed, it might hinder opportunities for the other Afro-Americans.”

Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby became and stayed friends, often talking on the phone and supporting each other through the extraordinary pressures that included open hostilities from some team members, opponents and fans. Doby, without the months of preparation that helped Jackie Robinson endure his ordeals, endured two ordeals of his own. The first involved his entry into a hostile world where many wanted him to fail, and the second was being ignored by history because he was not the first to enter that world. Doby endured both without complaint, never saying anything about Jackie Robinson that could be construed as even hinting at jealousy. Even casual baseball fans know about Jackie Robinson, yet how many could name Larry Doby as the first black player in the American League? With quiet pride and dignity, he always expressed his admiration for and his gratitude to Jackie Robinson for making it possible for him to have a baseball career as a pioneer in the American League.

Larry Doby had what can only be described as an exceptional career as that pioneer in the American League.

- 7-time All-Star

- World Series champion with 1948 Indians

- First player to go from the Negro Leagues straight to the Majors

- First black player to hit a home run in the World Series

- First player to win championships in the Negro Leagues & Majors

- First black player to win a home run title in the Majors

- First black player to win an RBI title in the American League

It took many years for Doby to finally begin to receive the recognition he had quietly earned. In 1997, the Cleveland Indians retired Doby’s number 14 on the 50th anniversary of his major-league debut, making him the fifth Cleveland player to be so honored. He joined Bob Feller, Earl Averill, Mel Harder, and Lou Boudreau who previously had their numbers retired. A banner was displayed in left field on July 5, 1997 at Jacobs Field showing Doby and Jackie Robinson along with the caption: “50 years: 1947-1997.” The 1997 All-Star Game in Cleveland was dedicated to Larry Doby. He served as the honorary American League captain and threw out the first pitch for the game. About half a million dollars from the All-Star proceeds went to building a playground project in the city where he first played, the Larry Doby All-Star Playground. Finally, in July 1998, the Veterans Committee awarded a long overdue recognition, induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Doby was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1998. (Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Lawrence Eugene Doby, baseball icon, died on June 18, 2003. He was 79 years old.

July 5th, 2013 at 6:00 am

July 5th, 2013 at 6:00 am  by Harold Uhlman

by Harold Uhlman

Posted in

Posted in

I love that picture of Jackie and Larry. Talking about playing with “heart”.

If Bill Veeck had not shared his plan for black players with Landis and become the owner of the Phillies, it is anyone’s guess who the first black player in the modern era would have been. My guess – Satchel Paige – as Larry was still a teen then and Veeck apparently wasn’t all that impressed with Jackie. Maybe he would have brought several young players in at the same time.

Another good one, Harold. I had fun doing the graphics for this one and I hope you approve of the 14/42 angle.

I have to admit that Veeck’s idea of either having several blacks debut at the same time (which didn’t happen because of Landis) and/or having Doby just show up one day unannounced (which did happen) was probably better for Doby than pre-announcing or even showing off a black player in the minors for a year (as Rickey did with Jackie Robinson) probably lessened the verbal abuse a little for Larry, but he obviously still took a ton of it.

I agree that if Veeck had kept his mouth shut with the press and had taken Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson seriously (i.e. why would the Dodgers even have him in Montreal if they weren’t planning to bring him up to the Bigs relatively soon), we’d probably be standing in line to see “14” instead of “42” on April 12, 2013.

Thanks for another fine article Harold. I have to say, I’m a lover of the past, especially baseball’s past. Although the Larry Doby story was no stranger to me, again you brought up a lot of the background of a player that I’ve never read before. It’s great to read many of these stories in the TBLA blog. Thanks again.

Jackie was fortunate to have played in Montreal where he was adored, but half of his games were on the road. So in a way Rickey’s plan wasn’t too bad as it gave Jackie a fair amount of time when he wasn’t under the extreme pressure. I expect he was testing to see if Jackie could handle the difficult times in the International League. Whatever the process, they both excelled.

Jackie in Montreal

Like the “14” – wish I had thought of it.

Great article Harold !! After hearing what Jackie went through I don’t see how any other black player could have survived. He was one of a kind !!

Re-post from January 25, 2013 on this historic anniversary: “14” – The Other Jackie Robinson” – http://t.co/1QsK8P8YTz #Dodgers #Dodgerfam

Now how did you remember this date in baseball history?

They have this new invention called Twitter.

Veeck asked Ray Dandridge before Larry Doby, but he turned it down b/c of his salary in Mexico. @Think_BlueLA http://t.co/HpR3HTZ3ka