“Nice guys finish last.”

It is a phase that everyone has heard and probably even said at least once in their life, perhaps even many times. But only those with graying hair or (in my case) very little hair know of its origin.

Ironically, the phrase was actually coined by a baseball man; a man who, like the phrase itself, almost everyone has heard of but know little about. His name was Leo Ernest Durocher.

Born on July 27, 1905 in West Springfield, Massachusetts, it is fair to say there have been few characters in the 130-year history of major league baseball that were more colorful than Leo Durocher.

Durocher’s baseball career began in 1925 when he was called up briefly by the New York Yankees as a shortstop. After being sent back down to the minors, Durocher was finally called back up to stay in 1928, having just missed out on the famous 1927 Yankees team, perhaps the greatest team in baseball history. Although Durocher was very good with the glove, his hitting was anything but spectacular. In fact, his teammate Babe Ruth nicknamed him “The All-American Out.” (The relationship between Ruth and Durocher went downhill rapidly from there, but we’ll get to that a little later).

Despite the friction between Ruth and Durocher, Leo was well liked by Yankees manager Miller Huggins, who often said that he saw the seeds of a great manager in Durocher because of his competitiveness, his passion, his ego and his remarkable ability for remembering situations. However, Durocher’s outspokenness and his habit of passing bad checks to finance his expensive clothes and nightlife annoyed Yankees ownership, particularly general manager Ed Barrow. In spite of this, Durocher’s excellent defense helped the Yankees win their second consecutive World Series title in 1928; after which he demanded a raise but instead was promptly sold to the Cincinnati Reds.

After three uneventful seasons in Cincinnati, Durocher was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals where he was assigned uniform number 2, the number that he would wear for the remainder of his professional career. That Cardinals team was dubbed the “Gashouse Gang” and was led by Durocher. Unlike his time with the Yankees and Reds, Durocher was given full rein by Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey and his true personality as a fiery player and vicious bench jockey fully blossomed. Durocher was named team captain and remained with the Cardinals through 1937, collecting his second World Series title in 1934 – the third for the Cardinals in nine seasons.

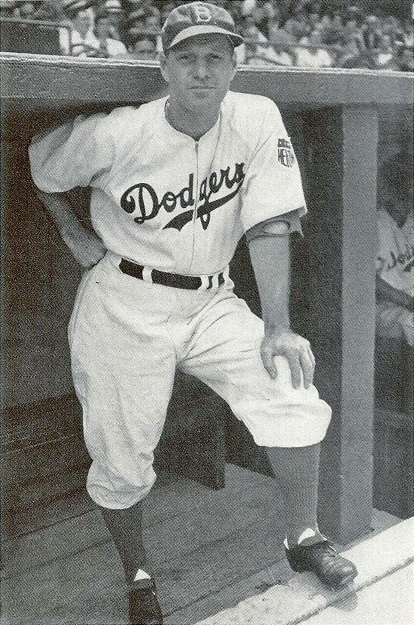

Durocher was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1938, where he continued to excel defensively. In June of 1938, Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail hired Babe Ruth to be a base coach. Ruth had been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame just two years earlier as one if its five inaugural members. Although MacPhail’s decision to hire Ruth was clearly a PR move to increase attendance at Ebbets Field, the Dodger GM had hopes that Ruth might replace current Dodgers manager Burleigh Grimes. Grimes was extremely popular among Dodger fans and it would take someone of significant popularity to replace Grimes from the fans’ perspective. Aside from that, there was nothing to even hint that Ruth had the skill or aptitude to be a successful coach or manager.

After a particularly tough loss one afternoon, Grimes followed his players into the clubhouse and came upon Durocher and Ruth in a heated argument. “Why you big stiff!” Durocher was screaming. “You can’t even remember the signs long enough to get from the bench to the coaching line! No wonder we’re getting piled up on the bases and balling up hit and run plays!”

Although the great Babe Ruth put fannies in the seats at Ebbets Field during his brief time as a Dodger coach, he simply did not have the skills to be a successful coach or manager.

(AP Photo)

The Babe wanted to fight and, of course, so did Durocher, but the much bigger Grimes separated the two and sent them to the showers. Although Grimes never mentioned the incident to MacPhail, somebody did and MacPhail shook his head and came to realize that his test of Ruth as a possible replacement for Grimes had failed miserably. Not wanting to create a publicity nightmare, MacPhail kept Ruth on as base coach until the end of the season when Ruth abruptly quit and would never wear a baseball uniform again. Burleigh Grimes was also let go as manager at the end of the 1938 season.

In 1939, Durocher was appointed as the team’s player manager by MacPhail and Leo’s popularity with the incessantly raucous Brooklyn Dodger fans grew tremendously – primarily because of Durocher’s frequent (very frequent, in fact) arguments with umpires, opposing managers, newspaper reporters and, most of all, with MacPhail, who reportedly fired and re-hired Durocher an estimated 60 times. (Billy Martin had nothing on Leo). Durocher’s frequent dirt-kicking, nose-to-nose arguments with umpires earned him both the nickname “Leo the Lip” and a total of 95 career ejections as a manager, which still ranks fourth on the all-time list. It also earned him countless fines and an occasional one to five game suspension.

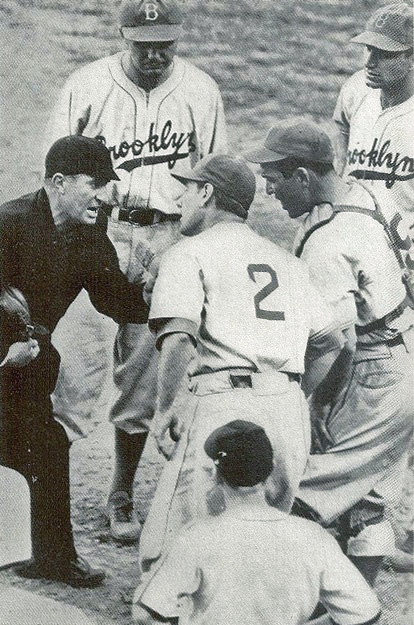

During a game against the Pirates in 1941, umpire George Magerkurth called a balk on Dodgers pitcher Hugh Casey causing Durocher to explode from the dugout and get into a tirade against the umpire. Durocher was quickly joined by half a dozen of his players and the entire lot of them were ejected from the game.

Durocher received a $150 fine when he and six of his players argued a balk call with umpire Frank Magerkurth. The fine would not be the last of this incident, however. (International News photo)

Several days later in while in Philadelphia for a series against the Phillies, Durocher received word from National League President Ford Frick that he had been fined $150 for the incident in Pittsburgh and his six players fined a lesser amount. Durocher was sitting in the hotel bar still stewing about the injustice (as he called it) and decided to go out for some air. Once outside, Durocher was confronted by a reporter named Ted Meier from the Associated Press who wanted a statement from Durocher on the Pittsburgh incident, which was the very last thing that Durocher wanted to talk about. One word led to another and the two adjourned to a nearby alley and in spite of being outweighed by some thirty pounds, Durocher flattened Meier three times. Just as Meier was getting to his feet after the third knockdown and before the scuffle could continue, a cop suddenly appeared.

“What’s going on here?” the cop demanded to know.

“Nothing, officer,” said Jerry Mitchell, a reporter for the New York Post. “It’s only that the Dodgers are in town.”

“Oh,” the cop said as he turned and walked away.

With peace having been restored, Durocher and Meier shook hands apologizing to one another and Durocher gave Meier the story he wanted. Nothing more was ever said of the incident.

Durocher led the Dodgers to the NL pennant in 1941 with a 100-54 record in only his third season as manager. It was the Dodgers first trip to the World Series in 21 years. But like so many times before, the Dodgers came away without a World Series championship, losing to the Yankees in five games. Durocher followed up that remarkable 1941 season with an even more impressive 104 wins in 1942, only to finish two games back of the St. Louis Cardinals.

At the conclusion of the 1942 season and at age 52, Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail shocked the baseball world. Instead of accepting the $75,000 a year/five-year contract that he had been offered by the Dodgers, he instead re-enlisted in the Army simply saying “It’s the right thing to do.” Few people would have done what MacPhail did and it clearly showed what type of a man he truly was. MacPhail was replaced by Branch Rickey as the Dodgers new general manager. MacPhail would later return to baseball as part-owner of the Yankees and was eventually inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

During a July 6, 1946 interview with Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber, Durocher made a comment about his belief that if a team’s players got along well, they would naturally play better than teams that did not. Durocher noted that several Giants players had reputations as being very personable, most notably manager Mel Ott. Durocher mentioned to Barber that they were all “nice guys,” but they (the Giants) would nonetheless finish in last place (this while his Dodgers were in first place in the National League). Durocher summed up his argument by saying “Nice guys; finish last.” As might be expected, Durocher’s comment created quite a stir in the baseball world and reporters had a field day trying to express exactly what Durocher had meant by his comment. But regardless of its interpretation, the comment became immortalized when is was entered into “Barlett’s Familiar Quotations” and is indisputably attributed to Leo Durocher.

Durocher’s tenure with the Dodgers was definitely not without significant controversy. His association with known big-time gamblers and bookmakers (and reportedly even notorious mobster Bugsy Siegel), coupled with his own penchant for gambling, caused Baseball Commissioner Albert “Happy” Chandler to suspend Durocher for the entire 1947 season; and every baseball fan knows how important the 1947 season was for the Brooklyn Dodgers – it was the year that Jackie Robinson made his major league debut, thus breaking baseball’s color barrier.

Prior to Durocher officially leaving the team to begin his suspension, he witnessed ugly dissention in the Dodgers clubhouse over Jackie Robinson joining the team, thus causing Leo to say what are perhaps the most important words of his life: “I do not care if the guy is yellow or black, or if he has stripes like a fuckin’ zebra. I’m the manager of this team, and I say he plays. What’s more, I say he can make us all rich. And if any of you cannot use the money, I will see that you are all traded.” Leo greatly admired Robinson for his hustle and aggressiveness, once calling him “a Durocher with talent.”

Durocher returned to the Dodgers after his suspension for the 1948 season, but his outspoken personality and poor results on the field caused friction with Rickey. On July 16 of that year, Durocher, Rickey and New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham negotiated a deal that let Durocher out of his Brooklyn contract to become manager of the cross-town rival Giants. Durocher enjoyed what was undoubtedly his sweetest revenge against his former team in 1951 when the Giants beat the Dodgers to win the NL pennant on Bobby Thomson’s historic “shot heard ’round the world” game-winning home run.

In 1954, Durocher won his only World Series championship as a manager when his Giants swept the heavily favored Cleveland Indians, who had posted the best American League record of all time (111-43) in the regular season.

Durocher left baseball after the 1955 season and remained out of the game until hired by the (now) Los Angeles Dodgers in 1961, where he served as a coach. While with the Dodgers, Durocher picked up his fourth and final World Series title in 1963. He left the Dodgers after the 1964 season.

In 1966 Durocher became the manager of the Chicago Cubs where he remained until 1972. He went on to serve as manager of the Houston Astros for the 1973 season, after which he ended his career in the MLB. He later served as manager of the Taiheiyo Club Lions in Japan for one year in 1976.

Durocher finished his managerial career with a 2008-1709 record for a .540 winning percentage. He posted a winning record with each of the four teams he led and was the first manager to win 500 games with three different clubs. Durocher was a three-time All-Star (1936, 1938, 1940) and a four-time World Series champion, twice as a player, once as a manager and once as a coach (1928, 1934, 1954,1963).

Leo Durocher died on October 7, 1991 in Palm Springs, California at the age of 86. He was posthumously inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1994, having been voted in by the Veterans Committee.

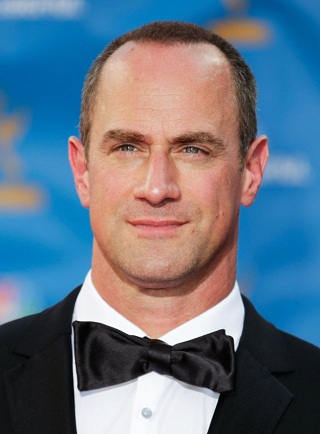

Actor Christopher Meloni will portray Leo Durocher in the upcoming movie 42.

February 5th, 2013 at 7:00 am

February 5th, 2013 at 7:00 am  by Ron Cervenka

by Ron Cervenka

Posted in

Posted in

Wow, Ron. Nice research and history lesson. I now know more about Leo Durocher than I ever have. He sounds like he was “the Dodger way” kind of player and manager. Thanks for putting the pieces together for a great story!

Thanks Kevin. Leo was quite a character and his frequent firings and re-hirings by MacPhail were quite comical and the source of countless great stories in the book The Brooklyn Dodgers – An Informal History, which was written in 1945. This great book tells of the remarkable history of the Dodgers from their very beginnings as far back as 1849; a history that, for the most part, has been lost except by the truest of Dodger fans.

I encourage every serious Dodger fan to read this absolutely wonderful and easy-to-read book.

As many of us can say ” I knew the name but not the real story” thanks for making me a little more knowledgeable Ron !!

Good story – Leo was always good for one.

He could make news. He married actress Laraine Day, who became known as the “The First Lady of Baseball”, under unusual circumstances.

Even as a youngster he ticked off Ty Cobb who was playing with the Philadelphia Athletics at the time. Although the hip check he is reputed to have given Cobb is untrue, he certainly got under Cobb’s skin.

Not too many baseball players become “characters of the game” like Leo. Love him or hate him he kept the game in the news and did have a good career as a manger.

Great article, Ron. Leo was involved in so many great moments in baseball history. It was his ’69 Cubs that lost the NL East title to the ’69 miracle Mets.

Thanks Ron, It’s always good to read a chapter in Dodger history. Durocher was the Dodger manager when I became a fan.

I recall when the Giants asked Rickey if they could talk to Shutton after Durocher returned to the team. Rickey said, “No, but you can talk to Durocher”. This was one of the first disappointments I got as a Dodger fan. It really was a shock.

Rickey and Durocher were constantly at odds with one another and, for the most part, simply tolerated each other. But Rickey was smart enough to realize that the Brooklyn fans loved Durocher and, as such, Rickey felt pressured to keep him on as manager. But when Durocher was suspended for the 1947 season and the Dodgers won the pennant without him, Leo had fallen out of grace with the fans and Rickey no longer felt obligated to keep him. This is what led to the deal being struck in the middle of the 1948 season to send Durocher to the Giants.

After reading The Brooklyn Dodgers – An Informal History and The Boys of Summer, I absolutely cannot wait to see the movie 42. I am curious to see how Durocher is portrayed. My guess is that because of the clubhouse incident, he will be portrayed very favorably.

can I buy a copy of the Babe Ruth Dodger photo?