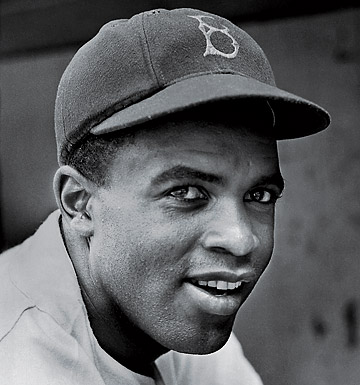

It seems like what, maybe 15… 18… 20 years ago tops, but it was actually 40 years ago today that the one man who had the single biggest impact in the 136-year history of major league baseball passed away. I am, of course, speaking of the great Jackie Robinson, who died of a heart attack at his home in Stamford, Connecticut on this date in 1972. Jackie was only 53 years old.

So much has been written and spoken about Jackie Robinson that there is absolutely nothing that I can add to his importance to our nation and perhaps the entire world, with one exception – what Jackie Robinson meant to me.

Having been born in 1953, I was unaware that Jackie had already broken baseball’s color barrier. In fact, it wasn’t until I was five years old and joined my very first Little League team that I had even heard the name Jackie Robinson. But over the course of the next year and because my very first Little League team was called the Dodgers, I began taking an interest in what people called The Boys of Summer. I remember thinking to myself “These guys aren’t boys, they’re grown ups.” And even though, at age five, I had far more important things to think about (such as recess and what the cafeteria was serving for lunch), I knew that the Dodgers were special because I was a Dodger.

When the Dodgers made the move west in 1958, my father, who had been born and raised in Chicago and who was an avid Cubs (and Bears) fan, took my brothers and me to the L.A. Memorial Coliseum to see the real grown-up Dodgers. It was here that I first laid eyes on the guys who I had heard so much about. They were right there in front of me… The Boys of Summer. I was ecstatic! Of course by this time, there were several black players on the Dodgers, most notably Junior Gilliam, John Roseboro, and Don Newcombe. But I also noticed who was not there.

“Where’s Jackie Robinson?” I remember asking my father. “He retired,” I remember my dad telling me. “What’s that mean?” I asked. “It means he no longer plays baseball,” my dad patiently added. “Why?” I asked (you can see where this one is headed – if you ever had kids, that is). “Because he is too old,” concluded my dad, although too old to play baseball didn’t really make any sense to me – it was, after all, just a game.

Another thing that I noticed while at this and subsequent Dodgers games that my father took my brothers and me to was that most of the people in the very large crowds were like me, Caucasian – even though I had no clue what that word mean at the time. I noticed that there were very few Negroes (as they were called at the time and definitely not in a disrespectful way whatsoever). I need to point out that I was born and raised in the (then) nearly all-white city of Burbank, California, a suburb of Los Angeles located in the San Fernando Valley.

As an unknowing youngster, I knew no distinction (nor did I even care) that people were Black, White, Hispanic, or of any other race. I had no idea what the color barrier even was because it meant absolutely nothing to me. The only distinction that I knew was kids (boys and girls) and grown ups (men and women) – that’s it, nothing else mattered. In the late 50’s and early 60’s the only barrier I knew of was the sound barrier – this because the Lockheed Aircraft Company was located in Burbank and their U-2 spy planes frequently took off from what is today called Bob Hope Airport but was Lockheed Air Terminal at the time. These remarkable planes frequently broke the sound barrier with a loud and ground-shaking sonic boom (it was really cool!). To me the only color barrier was the box that we put our crayons in.

It wasn’t until 1965 at the still tender age of 11 that I learned what the real color barrier was – and let me tell you, it was it a very rude and very ugly awakening. The date was August 11, 1965, a mere 29 days before Sandy Koufax pitched his perfect game at Dodger Stadium; a game that to this day is still arguably the greatest game ever played; a game in which five of the nine Dodger players in the starting line-up (including catcher John Roseboro) were black. It was the day that the Watts Riots began and a day that changed Los Angeles forever.

It took six days for police and National Guard troops to restore order in Los Angeles during the Watts riots. (AP photo)

As I look back on that horrible time in history (and not just L.A. history), I finally understood that there was still a color barrier, but what I didn’t understand, of course, was why. I had seen firsthand that people, kids and major league baseball players (grown ups), could work (and play) together as a team regardless of their skin color; teams such as the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Los Angeles Dodgers, and even the St. Francis Xavier Dodgers (my Little League team).

I can only imagine how Jackie Robinson must have felt during this awful time, especially when you consider what he had gone through and the fact that he had attended John Muir High School in Pasadena and UCLA in West Los Angeles. He must have felt as though everything he had endured and the personal sacrifices that he had made had been thrown out the window in a matter of six days.

Fortunately, in the years following the Watts Riots (and a few others) and through Civil Rights reform and legislation, our country slowly began the long, hard road to integration. And even though there is clearly still racism in our society and probably always will be, can you imagine where we would be today had there never been a Jackie Robinson?

Although today’s anniversary is a sad one, it is most certainly a huge one; one that should never be forgotten.

Thank you, Jackie, thank you.

October 24th, 2012 at 2:25 pm

October 24th, 2012 at 2:25 pm  by Ron Cervenka

by Ron Cervenka

Posted in

Posted in

You know how I feel about Jackie. Some time ago the question was asked with whom we would like to have dinner, if we could, living or dead. I said my Dad first, and then Jackie Robinson.

I didn’t know Jackie, Campy, Newk, Jim were black until I saw them on baseball cards in 1954 or so. There were no black people in Lunenburg but Jackie’s color made no difference to me. He was a baseball player, and more importantly, a Dodger baseball player. Only later did I learn about Jackie’s contribution to the game and to the social structure in the US.

Nice article and reminder.

Yes 40 years doesn’t seem that long ago after all it was only 1972. I was married for seven years at the time and had one child.

I remember it was a very sad day. Jackie was one of my favorite heroes, if not my favorite.

I remember when he broke the color line and at that time I was 9 years old. I wasn’t old enough to realize what he had done but as I grew older and learned the history of the game, I knew.

Now I know how important he was, not only in baseball and to the Dodgers, but in life.

You all know how I feel about Jackie, from my signature picture. Once again I am so very proud to be Canadian, when the great people of Montreal had such an important role in Jackies career. With accepting him for who he was.